I recently read Graham Weaver’s blog about why he started Alpine. Like Graham, I started my career in investment banking, and saw things I wanted to do differently in my career. What he wrote inspired me to write about my career path, and how the experiences along the way led to Razorhorse.

Entrepreneurs Change their World

As an employee, you can complain about how things are and talk about how things should be, but you have very little ability to create the world you want. As an entrepreneur, if you’re willing to take on unreasonable levels of risk, and you’re willing to do every job from the most menial to the most meaningful to achieve your vision, you can create a culture, a team and a client base that reflects your values and beliefs. That’s what I’ve been fortunate enough to do at Razorhorse.

I like to build, innovate, learn, teach, mentor, influence and win. I don’t care much about material things. For me, money buys freedom and experiences.

In college, when most of my peers were fighting for internships on Wall Street or with consulting firms, I owned and ran a painting business. I had to buy equipment, hire people, market and sell jobs, and manage three crews of painters. I wrote an honors thesis on what I learned.

Prestige and Money

In my senior year, a friend told me how much money I could make in consulting or investment banking. While I did well with my painting business, I was drawn to the prestige and money in those fields. So I signed up for some consulting interviews.

I got mowed down not realizing I needed to prepare for interviews. After all, I had a high GPA and I ran a successful business! Who wouldn’t want to hire me? Why should I need to estimate the number of bowling pins in the United States to get a job?

You’re Not a Consultant; You’re a Banker

I learned from a senior consultant who interviewed me that I had the aptitude for consulting, but not the demeanor. He told me I was an investment banker, and told me I wasn’t going to get an offer in consulting. So, I focused on banker interviews and started getting offers.

Well, You’re not Really a Banker Either

As a banker I learned I wasn’t a banker either, demeanor notwithstanding. I could do the work, but I questioned all the analyses and conclusions. I had more of a buy-side mentality than a sell-side mentality. So I went to the buy-side and worked for a banking client we took public where I did a mix of M&A and operations. There, I was reminded that I’m part operator as well.

Maybe You’re a Sales Guy

After business school I was supposed to go into venture capital, but the tech world blew up. It was 2001. So on the advice of two successful CEOs I had worked for, I got a job in sales. The only tech company that would hire me to do sales in the aftermath of the tech bubble bursting was IBM, where I learned I loved sales, but was not at all cut out for big company life.

In my first year at IBM, I tripled the revenue in my territory, but came short of my quota. I was dropped into the Wall Street sales team, the most coveted and competitive software sales group at IBM, with no sales experience and a fancy MBA. My manager dumped excess quota on me, lowering the quota for others on the team. It was a form of hazing.

In my second year, I was recruited to another team, and was able to exceed my quota. I also started producing my own sales collateral. I handed one pagers for the products I wanted to sell to the CIO of one of my clients, a Fortune 10 insurance company at the time. He liked them so much he asked for one on every software product IBM had. I ended up spending half the year that year meeting marketing teams at IBM in addition to my sales job trying to teach them how to replicate the one pagers I had created.

In my third year at IBM, I closed a big enterprise deal no one in my management chain thought could be closed. With that deal, I crushed my quota and I was offered a promotion. Instead, I took what I learned and got back to the buy-side. I did origination, then built an origination group while also focusing on deals.

Back to the Buy-Side

In VC and PE, I learned three things. First, the competence to ego ratio in those fields is structurally low. Second, and related to the first point, people either get lucky early, or languish. And third, deals are sold. I naively thought the best deals would sell themselves.

Competence to Ego Ratio

After twenty years in the industry, it’s clear to me that a balanced competence to ego ratio is actually a sustainable competitive advantage. That continues to surprise me, but it’s true. I see lots of firms claim to be some version of value added partners who understand the value is created by the entrepreneurs and operators. I’ve been fortunate enough to work with some people and groups where that is absolutely true, but they are outnumbered 10 to 1 by people and firms with upside-down competence to ego ratios.

Luck in Private Equity

In VC and PE, luck means working for talented, effective people who teach you the trade, and/or being fortunate enough to be even loosely affiliated with a successful investment or acquisition.

This is the challenge with an apprenticeship-based industry. Talent alone is not enough. You also need luck.

So, I started working on making my own luck. I had an opportunity to bet on myself and work for a successful entrepreneur turned buyer of software businesses. I ran a business for him for a year, learning a version of the Vista Equity playbook. Then I had the opportunity to buy companies for him. We sourced, won, negotiated, diligenced, and closed 30 deals for him in five years.

To do this many deals, I needed a lot of high-quality deal sourcing. So I sat down one Saturday morning in the beginning of our run, and I built the CRM capabilities I would need. Then we began building the origination flywheel.

I had built an origination capability twice before in my career — once in VC and once in PE. This time, I had a chance to own the IP. I built a function and a team that grew into a company — Razorhorse. I had an opportunity to bet on myself, forgoing any salary or retainer in exchange for a percentage of enterprise value closed, and in my first year I made more money than I would have made in three years in PE.

I finally got lucky, which I’ve come to realize is the intersection of preparedness, opportunity, and risk tolerance.

Deals are Sold

When I moved from sales to venture capital and private equity, I didn’t realize how important the enterprise sales skills I learned would be. I assumed, naively, that good deals sold themselves. Of course that’s not the case. Any investment or acquisition requires someone, and oftentimes multiple people on both sides of the transaction, to make a potentially career ending decision. Making up ‘smart’ reasons to pass on deals is easy. Determining what deals should be done, going out and winning them, and resolving to solve all the problems that come up during a deal process takes skill and risk tolerance. The big difference between sales and investing is that not all investments should be made. In sales, you qualify deals based on whether the customer has budget, and whether you think you can win. In private equity, you also have to disqualify deals that can be closed when negative diligence is uncovered.

Word of Mouth

As friends of mine saw the success we were having closing deals at Razorhorse. They started asking me if we could help them with origination. Our second client was an emerging growth equity firm I had partnered with in my days in PE. I knew their mandate and had brought them in on some deals.

They actually closed one of the deals our group sourced, even though my firm didn’t participate. As they finished investing out of their first fund, they needed to focus on fundraising for their second fund, and on building value add capabilities. They asked us if we could handle origination for at least one fund. We ended up sourcing half their deals for three funds, and the deals we sourced are some of the best deals in their portfolio.

Recovering from COVID

Slowly but surely, Razorhorse added clients, people I knew. Then when COVID hit, we lost half of our retainer revenue. We were liquid, and I had confidence in our model. So, we stayed the course and endured three months of losses and sleepless nights. We ended up taking on several new clients who saw the fear in the market as an opportunity to acquire more aggressively.

The owners of our new clients started bringing us in on more and more opportunities. They asked smart questions, and we endeavored to answer them. Our database and capabilities grew, and we started adding more and more talented people.

Network Effects

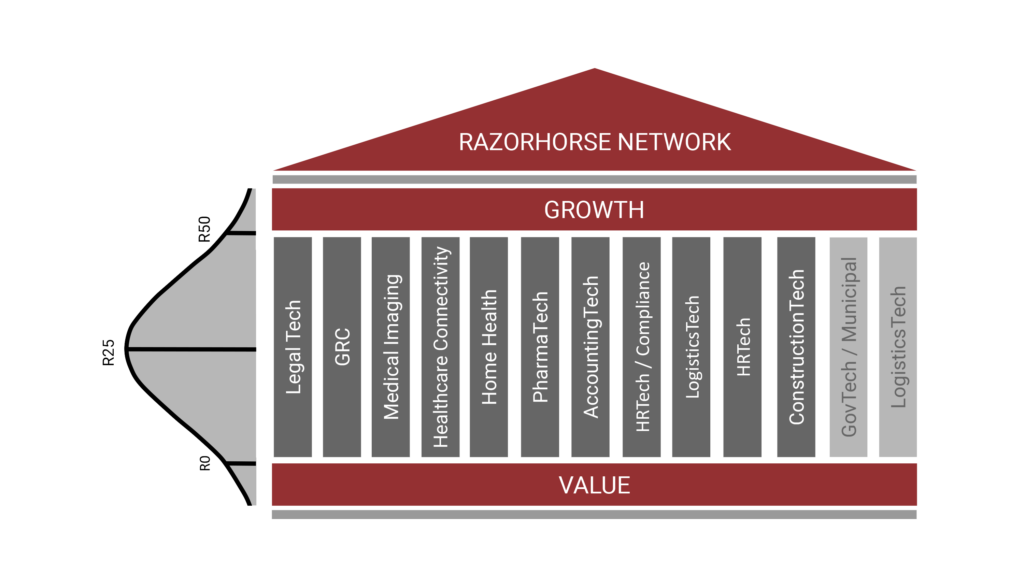

Today we have niche acquirers in addition to growth and value situational acquirers and investors.

When we look for companies in any given niche (the pillars in the house diagram), we find growth and value situations.

The Future

I never intended to build a services business at Razorhorse. I built a function, focused on process over outcome, and learned there was strong demand for what we do. My ultimate ambition is to spend more and more of my time as a customer of Razorhorse, producing deals with our partners and independently.

We’re hiring. Want to join the Razorhorse team? Browse our job openings.