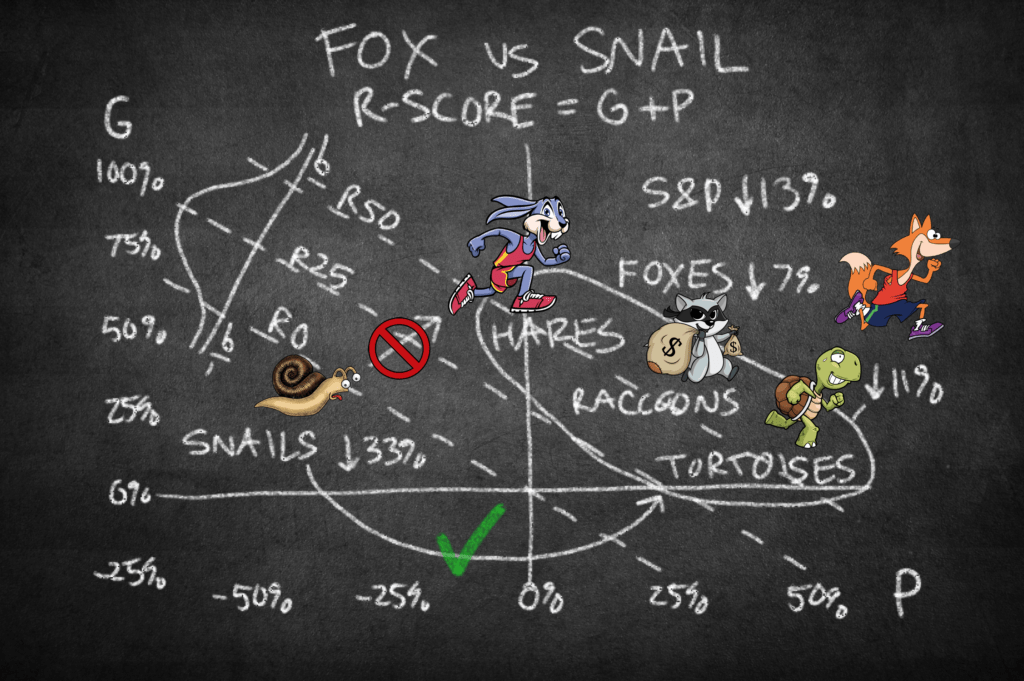

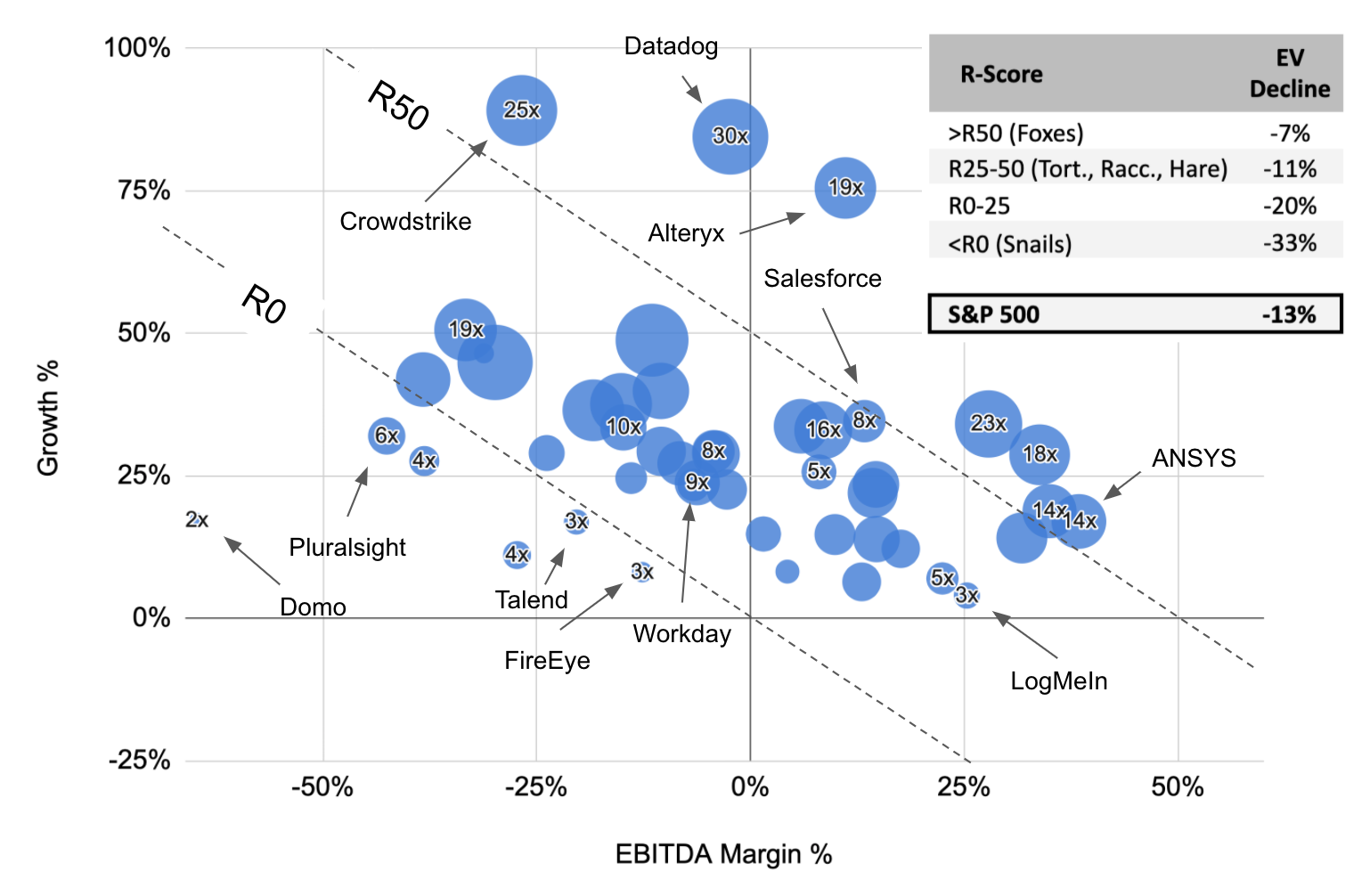

In January we hypothesized in “Tortoise vs. Hare” that companies with high R-Scores (Foxes) would be less impacted by a market downturn than companies with low R-Scores (Snails).

R-Score = Revenue Growth (“G” or “Growth”) + EBITDA margin (“P” or “Profit”)

With the impacts of COVID-19 rippling through financial markets, we are able to test that hypothesis against empirical market data. As anticipated, Foxes are weathering the Coronavirus storm better than Snails. So are Hares, Raccoons and Tortoises.

The S&P dropped 13% between January 31st and April 16th. Over the same period, our Foxes were down 7%, while our Tortoises, Raccoons and Hares (R25-50) were on average down 11%, in line with the market. Below R25, the impact of the downturn accelerates. Companies in the R0-R25 range lost nearly twice as much value as the S&P, and our Snails (R<0) lost value at 2.5x the rate of the S&P. This confirms our hypothesis. Snails are having a tougher time weathering the downturn.

Snails (R<0) lost value at 2.5x the rate of the S&P

In “I’m no Peyton Manning,” we cautioned that one of the biggest factors determining valuation for software companies is the market cycle. We observed that peak valuation multiples can be 2x valuation multiples in market troughs. Building on this observation, it’s important to note that stronger companies will be impacted less by market timing.

…stronger companies will be less impacted by market timing

Snail Survival Tactics

The good news for Snails is that they can transform into Tortoises. The bad news is, almost none do. They continue to pursue growth-at-any-cost strategies instead.

Tactic #1: Financing Burn with Multi-Year Prepaid Deals

Deferred revenue is one of the things we look at when acquiring a company with negative EBITDA. In a healthy recurring revenue business, deferred revenue should be about half of total recurring revenue. Seasonality can affect the ratio, and so can growth, but it’s a useful rule of thumb.

Deferred Revenue should be 0.5x – 1x ARR depending on growth and seasonality

Snails sometimes have deferred revenue balances that are 2x ARR or more. This happens when companies start offering multi-year paid-in-advance deals for discounts. This tactic is cheaper than debt, and a lot cheaper than an equity down round, but it impairs cash flow for an acquirer for years post-acquisition.

Tactic #2: Artificially Inflate Growth

Product swapping is another red-flag survival tactic we sometimes see. This is when two or more companies inflate their growth by selling their products to each other. This tactic is much harder to detect than multi-year prepaid deals.

We saw this tactic play out when one of our partners tried to acquire a VC-backed Snail. The company had grown 50% the year prior to acquisition, but they posted negative 80% EBITDA margins to fuel the growth, making them -R30. As the company ran low on cash, management was forced to cut costs, and growth slowed. Our partner valued the company at 2x revenue based strong product fit, and cost synergies. At that valuation, the VCs only got back a fraction of their investment, and outside of the carve out for the C-suite, there was nothing left for common shareholders.

During the exclusivity period, the company’s revenue retention started to deteriorate, and we learned it was primarily due to product swap deals with other Snails. Significant customers started to churn. In some cases, they had never deployed the software. Others renewed down significantly, because they had purchased more software than they needed.

When the renewal rate crashed, it became clear the growth was also inflated. Our partner had no choice but to walk from the deal. The company’s investors ended up liquidating the company a month later in an ABC (assignment for the benefit of creditors) process.

Tactic #3: Embrace Your Inner Tortoise

We worked with an R0 company that had flat growth, slightly negative EBITDA, and low retention rates for their category. Based on their KPIs, we thought they might be able to get 1.5x revenue in an exit. With 2.5x revenue in preference, that type of exit would have been a loss for the preferred shareholders, and a zero for common shareholders, including management.

We calculated unit economics, and found that new customer acquisition was unprofitable. We recommended that they stop chasing new logos, cut costs, and focus on their install base.

That was a tough pill to swallow, but the math was clear. We helped lay out the plan, and management executed it. After engaging with their most loyal customers, growth trended slightly up, they started generating positive cash flow, and retention rates improved. They ended up exiting for 3x revenue, which was by no means a home run for the investors, but it was a good outcome. If they had continued pursuing new logo growth, they likely would have sold for half as much. If they had doubled down to chase their initial Unicorn vision instead of embracing their inner Tortoise, they might have ended up in liquidation.

Moral of the Story

When there’s a choice between organic growth and profit, growth wins if the underlying unit economics are profitable. Companies with superior unit economics should operate at a loss. After all, a company growing 100% with negative 50% EBITDA margins is R50, a Fox. Some investors suggest the R-Score framework isn’t applicable until a company hits $15M in revenue. Others think the threshold is $50M. We think it depends on the business, and the ownership structure. A founder financed business in a small niche needs to think about the balance between growth and profit from day one. We see some founder-owned businesses with great unit economics operating at cash flow break even. If they can raise money on acceptable terms, they should operate at a loss as long as their unit economics hold up. A venture-backed business in a big market may be able to wait until they hit $50M in revenue before worrying about balancing growth and profit. Businesses with access to venture capital can sustain a deeper, longer J-curve than founder-owned businesses, but at the end of the day, unprofitable growth is unsustainable.